Anyone who has seen a newborn baby has marveled at the miracle of life and the seeming perfection of tiny human beings. Unfortunately, some babies only appear healthy at birth and have hidden, potentially dangerous health conditions.

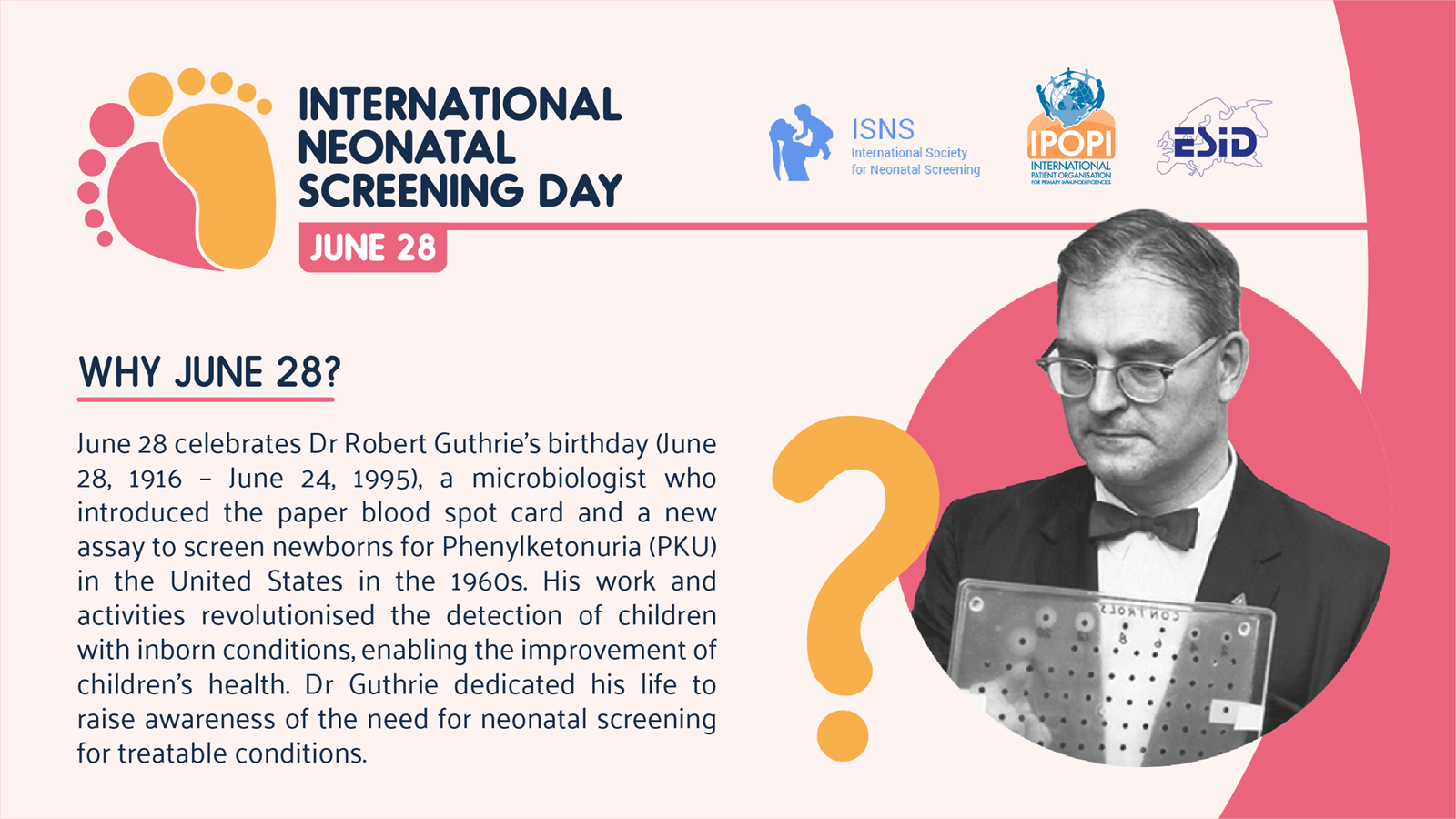

Enter Dr. Robert Guthrie, a microbiologist working in cancer research in the 1950s in Buffalo, New York, and also father of a son born with intellectual disabilities. Guthrie wanted to learn more about why mental disabilities occur. He met Robert Warner, Director of the Children’s Rehabilitation Center at Buffalo Children’s Hospital, and learned about the metabolic disorder, phenylketonuria (PKU).

Children with PKU had high levels of toxic phenylalanine, which eventually caused the intellectual deficits. But PKU, if caught early, could be controlled with dietary changes, sparing the child. A lightbulb moment followed when Guthrie thought he might be able to modify a bacterial inhibition assay he was using with cancer patients to test babies for phenylalanine, according to a 2021 article in the International Journal of Neonatal Screening.

“In short order he succeeded, so that there was now a simple and much more rapid method for measuring blood phenylalanine in patients with PKU,” wrote Harvey L. Levy of Boston Children’s Hospital.

But creating a simple newborn screening tool was only step one. Next, Guthrie had to convince the 1960s medical establishment that this test should be standard for all newborns. This early stirring of rare disease activism met with opposition because doctors believed PKU was too rare to justify testing thousands of babies. But Guthrie persisted, taking his argument to public health departments, training doctors and launching a national trial.

By 1962, 100,000 tests had been conducted and Guthrie showed that the incidence of PKU was more common than previously thought. Today, one in 10,000-15,000 babies in the United States tests positive for PKU and every state in the U.S. – as well as many countries in the world – test for PKU. With quick treatment, most people who have PKU now live healthy lives.

But Guthrie’s legacy extends well beyond PKU. He’s considered the father of newborn screening, which over several decades expanded its scope to include multiple conditions. Still today, the blood tests done at birth are called “Guthrie tests” and the cards they’re recorded on are called “Guthrie cards.” And when a coalition of public health advocates called Screen4Rare joined together to launch the first International Neonatal Screening Day, they chose June 28 – Guthrie’s birthday.

“June 28 is therefore a particularly auspicious day to celebrate the achievements of the concept that he helped both devise and promote,” organizers said in an announcement from Screen4Rare, which includes the International Patient Organisation for Primary Immunodeficiencies (IPOPI), the International Society for Neonatal Screening (ISNS) and the International Society for Neonatal Screening.

Rare disease advocates, including IPOPI and the U.S. Immune Deficiency Foundation, continue to campaign for newborn testing. The United States reached a milestone in 2018 when the last of the 50 states began testing routinely for Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), a catastrophic immune system condition that is fatal if not treated.

But there’s more to be done, IPOPI’s Executive Director Johan Prevot said in an interview earlier this year. Advocates continue to bring the issue to governments around the world with a goal of raising awareness and providing support, not imposing a one-size-fits-all approach.

“We hope that the International Neonatal Screening Day will become a real stimulus to raise awareness about the value of neonatal screening and encourage collaboration and best practices as a way of ever improving routine screening and incorporating of the newest scientific evidence,” Screen4Rare officials said.